Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

What is a Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)?

A Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) is caused by sudden and violent trauma to the head when (a) an object hits one’s head (b) one’s head hits on an object, (c) an object penetrates the head, (d) the head experiences rapid acceleration and deceleration without direct external trauma (e.g., whiplash), or (e) there is an event that generates forces to the head (e.g.. explosion). All injure the brain causing direct and indirect physical damage that disrupts brain function. Depending on which part of the brain is damaged, symptoms can be physical, psychological, emotional, and/or behavioral. Researchers have connected TBIs with depression, which is almost always accompanied by anxiety. They also have found that 48% of those with a TBI will develop PTSD.

(d) the head experiences rapid acceleration and deceleration without direct external trauma (e.g., whiplash), or (e) there is an event that generates forces to the head (e.g.. explosion). All injure the brain causing direct and indirect physical damage that disrupts brain function. Depending on which part of the brain is damaged, symptoms can be physical, psychological, emotional, and/or behavioral. Researchers have connected TBIs with depression, which is almost always accompanied by anxiety. They also have found that 48% of those with a TBI will develop PTSD.

There are links located in the credible resources section for more in-depth information about the subject matter in this section.

How is the brain injured?

Direct trauma (e.g., blunt trauma)

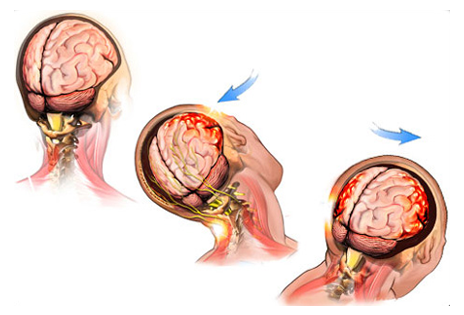

When the head is struck (e.g., baseball bat) or strikes something (e.g., pavement with a fall) the initial impact is called the primary injury also known as the “coup” injury. Specific symptoms will depend on where the impact occurs (e.g., the front of the brain involves the logic center, so damage to this area will involve problems with ability to make decisions and problem-solve). Be aware that many times there is a secondary site of injury called the “coutrecoup” injury, wherein the force of the impact accelerates the brain in the opposite direction slamming it against the skull directly opposite the initial impact. Many times this secondary injury can be more serious because the impact involves both the force of the initial impact plus the force generated by acceleration. Symptoms from the secondary injury site should be evaluated as well (e.g., the back of the brain involves the sight center, therefore a coutrecoup injury here may cause changes in vision, such as problems identifying words, colors, and objects).

Indirect trauma (e.g., head motion)

This type of injury occurs following forceful head movements (e.g., sudden acceleration and deceleration of the head from whiplash). It stretches and twists nerve fibers causing injury. Damage to nerve fibers affects how the brain communicates, that is, sends messages back and forth, thus altering or completely interrupting communication from one part of the brain to the other. Compare it to an electrical circuit. If the circuit is damaged, whatever the circuit supplies power to will exhibit decreased function. With a complete break in the circuit, there is no electricity running and whatever the circuit supplies power to stops completely.

Overpressurization (e.g., blast from an IED)

This type of injury causes diffuse damage to the brain as the pressure from the explosion causes sudden changes in the density of brain cells that damages their internal cell structures, and thus ability to function. There are four levels of injury that damage the brain (a) primary injury is direct harm to the brain cells from the blast wave, (b) secondary injury occurs as projectiles (e.g., shrapnel) from the blast enter the head, (c) tertiary injury occurs when one’s head is thrown onto fixed objects, and (d) quaternary injury occurs from inhaling toxic gases or when significant bleeding occurs from traumatic injury (e.g., amputation).

Since TBIs from blast injuries generally occur as a result of experiencing a terrifying and/or life-threatening event, someone who experiences a blast-related TBI is at increased risk of developing PTSD and depression/anxiety, and as such, should be evaluated for these disorders over time. These are important disorders to identify, diagnose, and treat because their presence prolong recovery and may affect prognosis (long-term outlook).

Closed versus penetrating TBI

These types of injuries cause different kinds of damage to the brain. With a closed-head injury the skull remains intact.The worst problems associated with this injury involve increased intracranial pressure from swelling or bleeding. These can be quite subtle with a mild TBI and therefore easy to miss, therefore symptoms like altered consciousness may occur later and should be monitored for over time.

With a penetrating injury the object either remains inside the skull or enters and then exits the skull (perforating injury). Primary injury occurs directly at the site where the object penetrated along with bruising, and damage to the nerve fibers. Secondary problems include swelling, infection, excessive bleeding, and lack of oxygen.

There are links located in the credible resources section for more in-depth information about the subject matter in this section.

How are TBIs classified as mild, moderate, and severe?

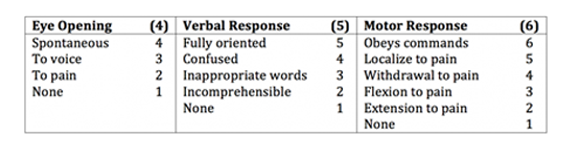

Classification system of severity is based on initial levels of disorientation and confusion as assessed in most cases using the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS). GCS objectively measures the level of consciousness in a person who experiences a TBI using a point scale according to level of function for ocular (eye), verbal, and motor (movement) responses. The highest score achieved, which indicates a fully awake and responsive person is 15. A low score of three indicates coma or death. GCS classifies TBIs as mild, moderate, or severe. The majority of TBIs are classified as mild (60-85%) with a GCS of 13-15 and are commonly referred to as concussions. Moderate and severe classifications each account for 10% of all TBIs with GCSs of 9 to 12 and 3 to 8, respectively.

The other common scale used to designate mild, moderate, and severe TBI is the Loss of Consciousness Scale (LOC), which uses the amount of time a person experiences LOC as the criteria. Mild has LOC of <20 min to 1 hour, moderate 30 min to 24 hours, and severe > 24 hours.

The other common scale used to designate mild, moderate, and severe TBI is the Loss of Consciousness Scale (LOC), which uses the amount of time a person experiences LOC as the criteria. Mild has LOC of <20 min to 1 hour, moderate 30 min to 24 hours, and severe > 24 hours.

There are links located in the credible resources section for more in-depth information about this subject matter.

What are the symptoms of a TBI?

Symptoms are generally sudden in onset, although they may have delayed expression with mild TBI or they may be missed when there is a more significant co-morbid injury (e.g., life-threatening- physical trauma). They may or may not worsen over time. Symptoms include:

- Headache

- Fatigue

- Nausea and/or vomiting

- Vertigo (dizziness)

- Tinnitus (ringing in the ears)

- Sensitivity to light and noise

- Difficulty Sleeping

- Decreased level of consciousness

- Loss of consciousness (includes presence and duration of unconsciousness)

- Loss of memory just prior to the event as well as after the event

Altered mental state as evidenced by:

- confusion and disorientation

- irritability/aggression/agitation

- forgetfulness

- apathy and no motivation

- mood swings and personality changes

- impulsiveness and decreased inhibition

- childlike/childish behavior (e.g., dependency, passivity)

- loss of sensitivity and concern

- depression/anxiety

Neurological deficits include:

- weakness

- changes in vision and speech

- loss of balance and sensory function

- lack of awareness/ poor concentration

- slowed thinking and behavior,

- poor organization/follow-through

- difficulty processing information

- inability to learn new concepts

- inability to use previously known concepts and skills

- Intracranial bleeding and/or bruising

Some of these symptoms may come and go. Additionally, the presence of some symptoms (e.g., lack of sleep) can make other symptoms (e.g., concentration, forgetfulness, irritability, and ability to cope) worse.

A group of late onset symptoms that are more serious effects from a TBI include: epilepsy, Post-Concussive Syndrome (PCS), and Major Neurocognitive Disorder (NCD) secondary to Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease.

There are links located in the credible resources section for more in-depth information about the subject matter in this section.

How are TBIs diagnosed?

TBIs are diagnosed by evaluating the type of injury and the extent of its effects. Assessment may consist of the following:

Physical exam in which you should provide as detailed a description of the event as you can and your symptoms pre, during, and post injury. Other sources important to providing a detailed history include others present during the event that caused the TBI as well as anyone who knows you and can describe your personality and behaviors prior to and after the event. Areas assessed include level of consciousness throughout the event, number of previous head trauma/injuries, level of cognitive ability before the event to document changes, and description of pre- and post-event personality and behavior. Multiple assessments should take place over time to evaluate presence of recovery or continued presence and/or worsening of symptoms that may indicate progression to Post-Concussive Syndrome (PCS) and Major Neurocognitive Disorder (NCD).

Screening measures such as Standardized Assessment of Concussion (SAC) and Mini Mental Status Exam (MMSE) are used in the civilian population and are used primarily to determine the need for further evaluation. The Department of Defense’s measure of choice is the Military Acute Concussion Evaluation (MACE), which is a brief screening tool that combines acute injury characteristics and symptoms documented in assessments with cognitive screening and neurological functioning exam results.

A report of ANY symptoms requires treatment and possibly prolonged light duty and any Service member diagnosed with mild TBI should be given 24 hours of down time to start and achieve full recovery.

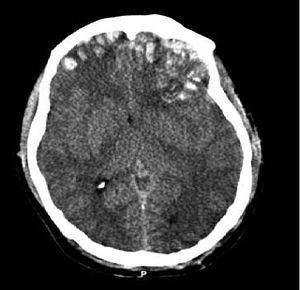

Neuroimaging studies,  such as MRI and CT scans, are generally reserved for moderate and severe TBI as these scans will oftentimes show normal brain structure in mild TBI. CT scans look for larger bleeds, whereas MRI scans can also find evidence of micro-bleeds.

such as MRI and CT scans, are generally reserved for moderate and severe TBI as these scans will oftentimes show normal brain structure in mild TBI. CT scans look for larger bleeds, whereas MRI scans can also find evidence of micro-bleeds.

Neuropsychological tests are conducted on individuals whose symptoms last more than 30 days to determine the full extent of the injury, such as if it is focal (one area of damage) or multifocal (multiple areas of damage). They are also helpful to confirm the diagnosis of post-TBI Major Neurocognitive Disorder (NCD). Testing should take place after the post-acute phase, approximately six weeks post-injury because Service members may not be able to tolerate the demands of these tests and the results may be invalid if conducted too soon. These tests are also helpful to establish baselines to compare results from repeat testing to evaluate for the effectiveness of treatment. These tests measure:

- Intelligence

- Attention and memory

- Cognitive processing speed

- Receptive and expressive language ability

- Visual-spatial organization

- Visual-motor coordination

- Executive functioning (regulation and control of memory, reasoning, and problem-solving)

What is the treatment and recovery process for TBI?

In terms of treatment, the injury to the brain tissue that occurred during the event that caused the TBI is not “treatable.” However, TBI-related symptoms are treated using a mix of patient education, management strategies, and supportive therapies planned and monitored by a multidisciplinary team of mental health providers. Initial treatment in the acute phase involves rest and light-duty with treatment for specific symptoms until the results from subsequent evaluation indicates recovery. For those who require further treatment, researchers have found that the treatments used for PTSD (e.g., Cognitive Processing and Prolonged Exposure Therapies) are effective as well for TBI. Other therapies may include:

Cognitive Rehabilitation has been shown to work effectively to reintegrate those who suffer from moderate to severe TBI back into the community, including returning to work. Early education and interventions are key to success. Rehabilitation therapies include occupational therapy and speech and language therapy.

Cognitive Rehabilitation has been shown to work effectively to reintegrate those who suffer from moderate to severe TBI back into the community, including returning to work. Early education and interventions are key to success. Rehabilitation therapies include occupational therapy and speech and language therapy.

Education for the Service member and Families focuses on emphasizing a good prognosis and the expected course of recovery. This is critical because it has been associated with reduction of symptoms. Normalizing symptoms and reactions post-TBI reduces fear and increases positive expectations. It is important that education include prevention of future TBI.

Symptom management includes:

Headaches - use massage, ice and heat, medications, and relaxing and stretching neck and face muscles.

Sleep hygiene – no caffeine, alcohol, nicotine, or strenuous exercise three hours prior to bedtime, keep bedtime routine relaxing and create an environment conducive to sleep (e.g., comfortable temperature, lighting, white noise, etc.), maintain consistent wake and sleep times, eliminate naps unless necessary (20-30 min only), go to bed when tired, but get up if you cannot go to sleep after 20-30 minutes, and take sleep medications consistently.

Memory problems – develop a routine, prioritize, write things down, get appropriate sleep, stay mentally and physically active, decrease stress levels, take in nutrients to feed the brain, and avoid alcohol, tobacco, energy drinks, and too much caffeine.

Balance/dizziness – modify activities, do not sleep on the side that sustained the TBI, if dizzy when standing, transition from sitting to standing slowly, change sleep position to semi-inclined, and do neck stretches and vestibular rehabilitation exercise.

Mood changes – ensure that symptoms are normalized via patient education, use cognitive strategies such as self-talk (e.g., identify negative thoughts and replace them with positive thoughts to change mood), use behavioral strategies (e.g., increase pleasant activities to change mood).

Stress management is important for those with TBI because the aftermath and its symptoms are inherently stressful. Use techniques that increase relaxation, such as meditation, biofeedback, deep breathing, and progressive muscle relaxation.

Treatment for those with moderate to severe TBI will be more intensive and may involve both inpatient and outpatient services. Treatment should be individualized, encourage independence, provide vocational opportunities when possible, strengthen areas of impairment, develop compensatory strategies, and involve the Family and caregivers.

Long-term recovery - Remember, 80% of Service members will suffer from mild TBI, only 50% of whom will be symptomatic. Most will achieve full recovery within days to weeks post-injury, provided that they are identified, diagnosed, and treated effectively. More specifically, 90-95% return to baseline functioning within 4 to 14 days. Most will experience complete resolution of symptoms by three months, although it can take up to 12 months. Rates of recovery differ from person to person based on the specifics of the injury, presence of other injuries from the event, and co-morbid conditions (e.g., PTSD). Also important to recovery time is the person’s response to the injury and perception that recovery is possible. It is important to remember; however, that symptoms can change over time, come and go, and tend to last longer for this population. It is essential for you to have assessments over a longer period of time to ensure your best health outcome. A small population (10 to 20%) will develop Post-Concussive Syndrome (PCS), which requires further and more intense treatment. There are risk and protective factors that influence whether or not a Service member develops PCS. Those with moderate to severe TBI may suffer from residual deficits; however, the goal of continued treatment is to help reintegrate the Service member into the community.

There are links located in the credible resources section for more in-depth information about the subject matter in this section.

Important points to remember

Most TBIs are classified as “mild” the symptoms of which will resolve over time if they are diagnosed and treated effectively. There are effective treatments for remaining symptoms that improve quality of life.

Remember that with closed impact blunt trauma, there is the primary injury at the site of impact that should be evaluated for symptoms and potentially a secondary injury on the other side of the brain directly opposite the point of impact, depending on the severity of impact. It is essential to evaluate for symptoms that result from this secondary injury because quite often, this injury is worse due to the forces of the impact itself plus the forces of acceleration of the brain from the impact.

It is important to understand that the severity of TBI does not necessarily equate to the development of Mild or Major Neurocognitive Disorder (NCD) or the potential for rehabilitation. In other words, no matter the initial level of severity your TBI is classified as, please remain hopeful that significant healing can occur. The path to recovery is different for each person and depends on other factors besides the initial level of severity. These factors include the person’s age, substance use, the specifics of the injury, prior history of TBI, presence of comorbid conditions like PTSD and depression, etc.

In order to advocate for yourself and others, remember there are mandatory requirements for evaluation for potential TBI, but unfortunately many are still being missed. Ensure your brain health by knowing that any Service member within 50 meters of a blast must be evaluated for TBI. TBI screenings prior to and after deployment are also mandatory. It is important that mild TBIs are diagnosed because research shows that Service members take longer to recover from TBIs, especially with repeated undiagnosed mild TBIs, which contributes to more severe symptoms and long-term problems.

There is significant relationship between TBI and PTSD and depression/anxiety. If you sustain a TBI that does not resolve in the appropriate amount of time, please have yourself evaluated for the presence of PTSD and depression/anxiety because early diagnosis and treatment vastly improves outcomes and quality of life.

There are links located in the credible resources section for more in-depth information about the subject matter in this section.

Credible Resources

The resources used for the information on our website were retrieved from Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center, Defense Centers of Excellence for Psychological Health & Traumatic Brain Injury, U.S. Department of Defense, and U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. However, the Matthew Patton Foundation is neither affiliated with nor endorsed by these organizations. Please use the following links for more in-depth information about TBI from these organizations.

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) at http://www.va.gov/QUALITYOFCARE/improving/Traumatic_Brain_Injury.asp http://www.research.va.gov/topics/tbi.cfm http://www.defense.gov/home/features/2012/0312_tbi/

TBI & the Military at http://dvbic.dcoe.mil/about/tbi-military

Management of Concussion/mild Traumatic Brain Injury at http://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/Rehab/mtbi/concussion_mtbi_full_1_0.pdf

Treating TBI at http://www.dcoe.mil/TraumaticBrainInjury/Tips_for_Treating_mTBI.aspx